Data Transaction Cookbook

Pattern Overview

Before diving in, we strongly recommend reading the Data Retrieval Cookbook

That cookbook establishes the core patterns for finding and shaping data skills this cookbook relies on. Once you understand how to retrieve objects deterministically, this guide shows you how to safely write updates back to your System(s).

Updating enterprise systems is deceptively hard. Users speak in loose natural language, while systems like ServiceNow, Workday, and Snowflake require precise, auditable, and fully specified writes. This cookbook explains how Agent Studio bridges that gap by turning intent into trusted system of record updates with writes that are safe, validated, and reversible where supported.

At the heart of this cookbook is the Data Transaction Pattern, a deterministic flow that every write operation should follow to stay consistent, compliant, and easy to reason about.

Core flow

- Identify the business object(s) to act on (via resolvers).

- If creating a record, initialize a new object.

- Set fields explicitly using validated slots, with preview & confirmation when appropriate.

- Commit the update to the system of record.

- Return a confirmation receipt back to the user.

This keeps updates correct, predictable, and audit-friendly, even when the conversation is ambiguous.

Example (simple update)

“Set INC0012345 priority to High.”

→ The system resolves the incident, validates the change, previews it, then writes:

Assistant preview:

“I’m about to change INC0012345 priority from Moderate to Critical. Should I proceed?”

Example (heavier multi-step)

“Reassign all open P1 tickets in EMEA to @jdoe and add a note.”

→ The assistant resolves the ticket set, then applies a series of targeted write operations. Updating owner, adding notes, and informs the user of the changes made.

This cookbook builds on that flow and expands it into a set of practical patterns you can reuse:

- When to use one plugin vs. multiple

- How to confirm or preview writes

- How to design multi-step, deterministic workflows

- How to fan out updates across many records

- How to handle conditional fields, hierarchical resolvers, and strict formats

- When to favor compound actions over conversational turn-taking

By the end, you’ll know how to design write flows that are:

- Deterministic: same inputs, same outputs

- Composable: small units the Reasoning Engine can orchestrate

- Auditable: every write is intentional and reviewable

- Safe: no unintended updates or silent failures

In short, this cookbook provides the patterns you need to build production-grade, system-of-record writes that users can trust and enterprises can depend on.

When to use one plugin vs. multiple to accomplish a change

Plugins should be atomic, predictable, and reusable. If one plugin can complete a change reliably, use one. If the change spans multiple distinct responsibilities, create multiple plugins and rely on the Reasoning Engine to call them for the user's needs. Avoid overly complex plugins when not necessary with needless paths and conversational turns.

Pattern A — Combined “resolve-and-write” plugin (with dynamic/static resolver that always prompts) (recommended in most cases)

Use when

- You want a single plugin to both find the target and perform the mutation.

- You still want the user to explicitly choose the record on every run (for safety/audit).

- Require an object as input/selection for your transaction

How it works in Agent Studio

- The mutation plugin includes a required slot for the target object (e.g.,

target_incident). - That slot uses a dynamic or static resolver that always returns a short candidate list and requires user selection before the write proceeds unless the user expressed a confident match in their intent from the resolver list.

- After the user selects, the plugin executes the write with an optional confirmation

Flow

- Single plugin returns a short candidate list (every run) to pick the target.

- User selects the record.

- The same plugin performs the single change.

Example: ServiceNow — change assigned_to (inline resolve + write)

Single plugin (resolve → Make the change)

Conversation

- “I need to reassign a ticket” → plugin shows up to 5 matching/recent incidents and prompts selection.

- User picks #2 and says “assign to @janedoe” → plugin updates

assigned_tofor the chosensys_id.

One Trade-off with this approach is it may add an extra turn in conversation depending on context

Tip: Keep the resolver’s list short and consistent in shape. This preserves token budget and keeps the selection UX fast and reliable. Filtering in the resolver helps here.

Pattern B — Split plugins

Use when:

- Plugin is filled with user provided data at plugin runtime or the output of another plugin for example a plugin to book a meeting that can be filled with a user provided time or the output of a plugin to find open meeting times.

- The input context is smaller context (simple primitive data types single string, integers)

Flow

- Lookup plugin returns a tight list (IDs + display fields).

- User (or resolver) selects the target.

- Write to System of Record plugin performs the single change on the selected record.

Example: ServiceNow — change assigned_to

Lookup plugin (returns incident info)

incidents:

MAP():

items: response.result

converter:

sys_id: item.sys_id

number: item.number

short_description: item.short_description

instructions_for_display: "Show up to 5 items as a numbered list."

Write to System of Record plugin (Set ticket owner and takes an incident sys_id and returns ticket id and new user assigned to)

id: data.incident_sys_id

new_user: data.new_assigned_to.external_system_identities.snow.user_id

Conversation

- “Look up my tickets.” → AI assistant list items #1–5.

- “Update the owner of #2 to @janedoe.” → mutation plugin runs with the corresponding

sys_id.

The reasoning engine is able to take the returned context of the initial plugin called and pass it into the 2nd plugin when the user asks because the return mapper of the 1st plugin returns the sys_id of all the tickets.

Writing multiple steps to retrieve data for a transaction

Some write operations require substantial upstream context that shouldn’t be left to probabilistic reasoning. Scheduling is a classic case. When a user says, “Book 30 minutes with Alice and Brian tomorrow afternoon,” the actual event creation depends on deterministic prep:

- Collect slots: attendees, time window, and duration.

- Run a compound action to:

- resolve people to canonical IDs,

- fetch each person’s availability for the window,

- compute the common free windows at a fixed granularity,

- return a compact list of candidate time slots (top-K).

- Present options in the conversation and ask the user to choose one.

- Call a separate booking plugin to create the event for the selected slot.

Because this workflow involves multiple network calls and set intersection logic across calendars, we implement it as a compound action. The reasoning engine gathers a few high value slots (attendees, window, duration) and receives only the final common availabilitysmall, structured output that’s easy to display or pass into another plugin.

If you embed every sub-call directly in a conversational process, each intermediate response is exposed to the reasoning engine, increasing token use and ambiguity. Prefer returning only the minimal result, which keeps context tight and improves reliability.

A good rule is any time you have multiple actions in succession that don't require additional input at each step is to use a compound action for those components.

Handling multiple updates across records

Users often ask for fan out writes, e.g., “Set all open P1 incidents in EMEA to Awaiting User and add a note,” or “Move these five opportunities to Negotiation and tag the exec owner.” The safest approach is to keep each plugin single-purpose (one record, one change to system of record type), then let the Moveworks Reasoning Engine plan multiple calls as needed. Avoid “mega-plugins” that attempt to infer targets, compute diffs, and apply heterogeneous mutations they increase ambiguity and conversational complexity.

Design rules

- One mutation per plugin. Make the plugin do a single, well-named change on one object (e.g.,

set_incident_state,update_opportunity_stage,toggle_feature_flag). - Let the Reasoning Engine fan out. The Reasoning Engine can call the same plugin many times for different records.

This is true for most scenarios, if the context is too large (trying to pass large structured objects with many fields or a very large amount of data 7k+ tokens) Then it is best to avoid letting the reasoning engine handle the updates.

The better approach in those scenarios is to use compound actions with for loops to deterministically make large updates to many records at once.

Example: ServiceNow - change state of many incidents

Intent: “For my open P1 incidents in EMEA, set state to Awaiting User and add a note ‘Pending customer response’.”

Plan:

- A unique plugin to retrieve all the user’s open Incidents and returns the sys ID of the ticket

- A unique plugin that can change the state of a ticket

Having one plugin that can return the list of the user’s open tickets and the details on them allows the reasoning engine to retrieve all the open tickets then it will call the plugin to change the state to Awaiting user for N amount of tickets

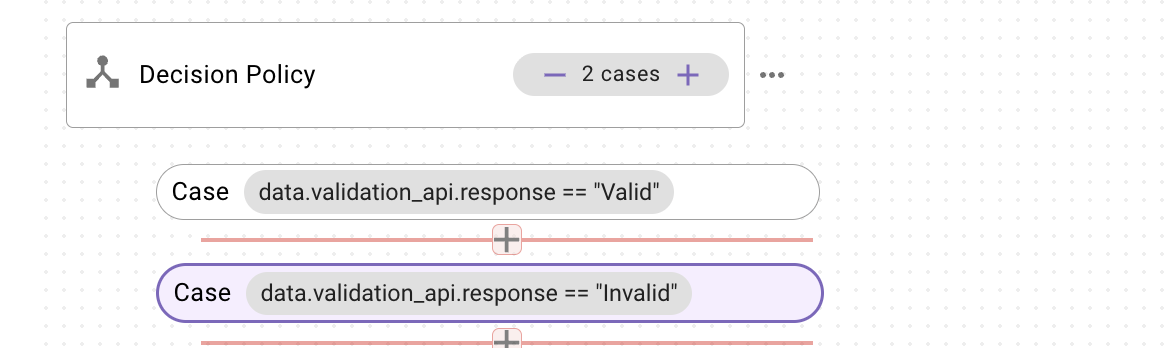

Conditional writes

Sometimes you may want to explicitly ask the user if they want to set an extra field —e.g., add an assignment group when creating or updating a ServiceNow incident. Most APIs expect either a concrete value (like a sys_id) or null/empty string. In Agent Studio, handle this cleanly by gating the write with a Decision Policy and a simple boolean slot.

How it works (pattern)

-

Ask intent, not value (yet):

Create a boolean slot like

does_user_want_to_add_assignment_groupthat captures whether the user wants to include the field. -

Branch with a Decision Policy:

- If

does_user_want_to_add_assignment_groupis False → call the action withassignment_groupset tonull, empty string (in yaml input args isassignment_group: ‘””’,(or simply omit the field, per your API’s semantics). - If True → collect

assignment_groupusing your Dynamic resolver (if you need to get a list of assignment_groups for the user to select from to get the associated id otherwise you could just take something like a string), then call the same action with that ID.

- Confirm before writing:

Keep comfirmation on for the action activity so the user can review which fields will be written, including when an optional field is left blank.

Slot Config

**name**: does_user_want_to_add_assignment_group

**data_type**: boolean

**description**: If the user would like to add an assignment group on the ticket then the value is true otherwise it is false.Decision policy

decision_policy:

conditions:

- when: NOT does_user_want_to_add_assignment_group

required_slots: [description, short_description]

- action: create_servicenow_incident

input_args:

assignment_group: '""'

description: data.description

short_description: data.short_description

- default:

required_slots: [assignment_group, description, short_description] # resolved to a sys_id via Dynamic resolver

- action: create_servicenow_incident

input_args:

assignment_group: data.assignment_group

description: data.description

short_description: data.short_description

Tips

- Default behavior: If most users skip the field, you could prompt the slot description to default

does_user_want_to_add_assignment_group = Falseand only make it true if the user explicitly provides it

Hierarchical resolvers: passing parent slot into child resolver

Use hierarchical resolvers when one Slot depends on another Slot’s value. This is accomplished with the context passing in resolvers feature.

Example payload: resolve a purchase_order first, then use that selection to resolve a line_item.

{

"purchase_orders": [

{

"id": "PO-1",

"vendor": "Acme",

"line_items": [

{ "id": "LI-1", "description": "Item A", "qty": 2, "unit_price": 10.0 },

{ "id": "LI-2", "description": "Item B", "qty": 1, "unit_price": 25.0 }

]

},

{

"id": "PO-2",

"vendor": "GlobalTech",

"line_items": [

{ "id": "LI-3", "description": "Item C", "qty": 5, "unit_price": 5.0 },

{ "id": "LI-4", "description": "Item D", "qty": 3, "unit_price": 12.0 }

]

},

{

"id": "PO-3",

"vendor": "OfficeMax",

"line_items": [

{ "id": "LI-5", "description": "Item E", "qty": 10, "unit_price": 2.5 }

]

}

]

}Use this pattern when:

- The user needs to select a parent object first, then a child object under it

- e.g. purchase order → line item

- e.g. country → region

- e.g. project → task

- The child resolver needs the actual object (or its ID) from the parent Slot, not just free-text.

High-level flow

- Parent Slot (e.g.

purchase_order) resolves normally using a dynamic resolver. - Child Slot (e.g.

line_item) has a strategy mapping whose method takes data from the parent as an input.

- On the child Slot, you configure Strategy Mapping so that:

data.purchase_order(the parent Slot value) is passed into the child resolver method input.

- The child resolver method’s Action reads the combined

dataobject (includes either:

- LLM-filled inputs via input args (e.g. search filters)

- Context-mapped inputs (e.g. the

purchase_orderobject)

Step-by-step: set up a parent → child resolver

Define the parent Slot and resolver (e.g. purchase_order)

- Create a

purchase_orderSlot. - Attach a Resolver Strategy that:

- Calls into your backend to list purchase orders for the current user.

- Returns a list the resolver UI can present.

- Configure the Resolver Method and its Action mapper as you normally would.

- No special context passing is needed here; this is just the first level.

Result: once resolved, the purchase_order Slot value is available on data.purchase_order at the Plugin level.

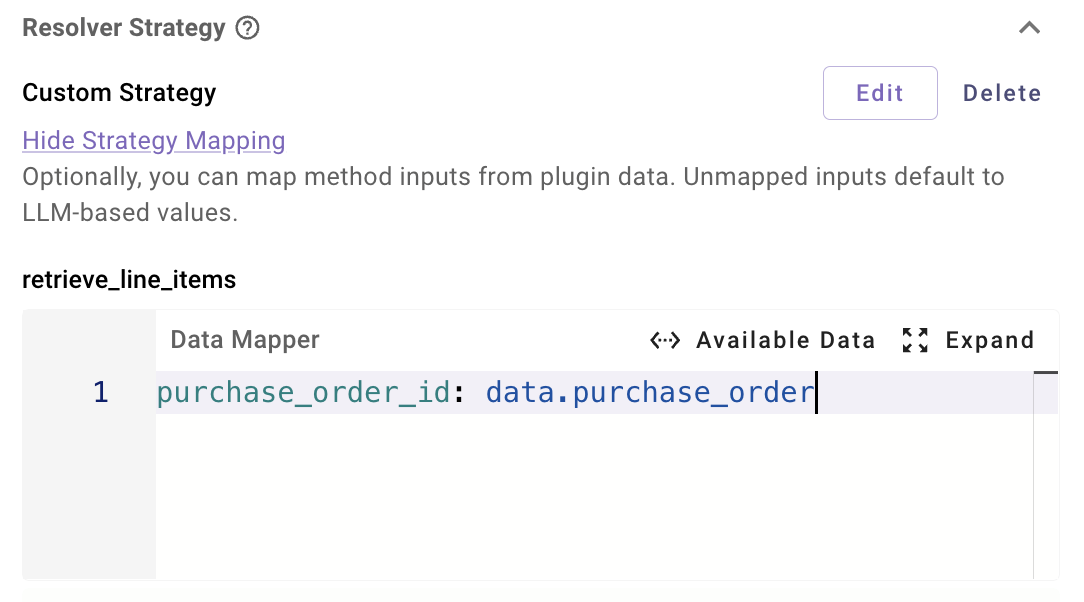

Define the child Slot’s resolver method (e.g. line_item)

Now create a Slot that depends on the parent:

-

Create a

line_itemSlot. -

Attach a Resolver Strategy with a dynamic Resolver Method, e.g.

select_line_item. -

In the Input Arguments JSON schema for

select_line_item:- Add only the inputs that should come from the LLM (e.g. a text filter):

{ "type": "object", "properties": { "search_query": { "type": "string", "description": "Search phrase to filter line items" } } }- The parent

purchase_orderinput is going to come from Plugin context, so it does not have to be included here.- If you want, you can include it (e.g.

"purchase_order": { "type": "string" }) for reuse, but it’s optional and will be overwritten with the mapped input.

- If you want, you can include it (e.g.

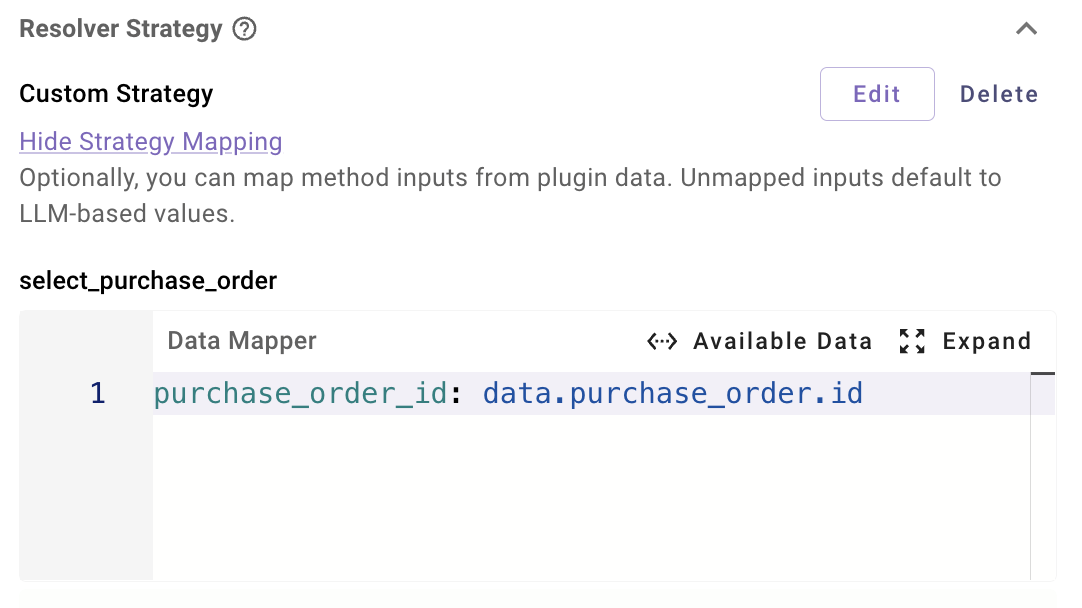

Map parent Slot into child resolver inputs (Strategy Mapping)

On the line_item Slot config:

-

Scroll to the Resolver Strategy section.

-

Click View Strategy Mapping.

-

Locate the mapper box for your

pick_line_itemmethod. -

Map the parent Slot into the resolver method input, e.g.:

# Strategy Mapping for method "pick_line_item" purchase_order_id: data.purchase_order.id

What this does:

- At runtime, when resolving

line_item, the system will:- Take the Plugin’s

purchase_order.idSlot value. - Inject it into the resolver method’s

purchase_order_idinput.

- Take the Plugin’s

- This is the “hierarchical” part: the child resolver always sees the selected

purchase_order.

You can also pass other context if needed for example:

purchase_order_date: data.purchase_order.date

user_email: meta_info.user.email_addrWire the child resolver’s Action input mapper

On the Resolver Method’s Action for select_line_item:

- Open the Action’s input mapper.

- Use

datato reference both:- Context-mapped inputs (e.g.

purchase_order_id) - LLM-filled inputs (e.g.

search_query)

- Context-mapped inputs (e.g.

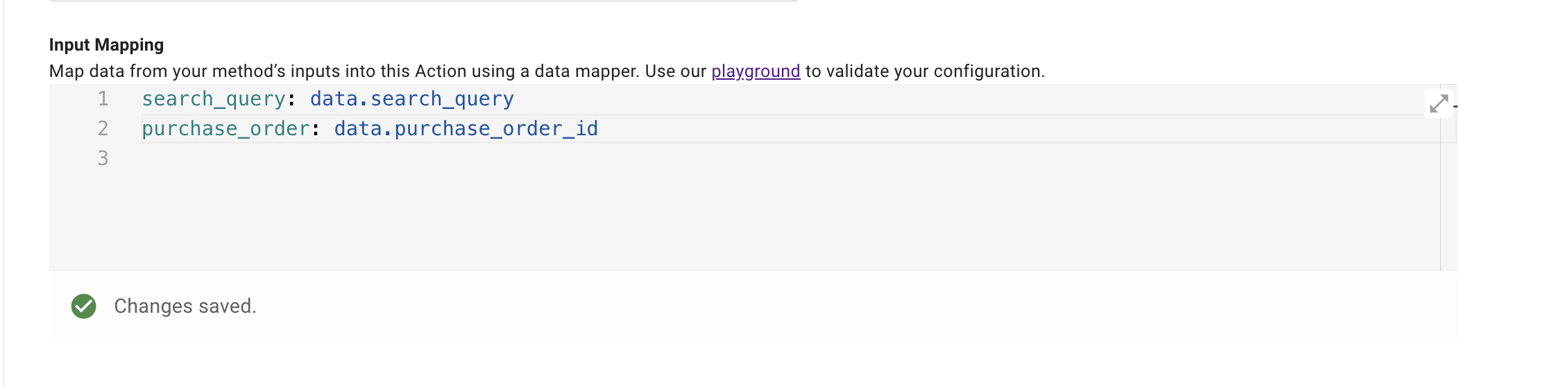

Example:

purchase_order: data.purchase_order_id

search_query: data.search_query

At this point:

data.purchase_ordercomes from the Strategy Mapping (parent Slot).data.search_querycomes from the LLM based on the Input Arguments schema.

Ensure correct Slot ordering

For this to work reliably, the parent Slot must exist before the child Slot tries to use it.

- Wherever

line_itemis required (Activity or Decision Policy):- Make sure

purchase_orderis selected as a required Slot beforeline_item.

- Make sure

- If you skip this:

data.purchase_ordermay be missing when Strategy Mapping runs, and the resolver or its Action may fail.

Handling strict data formats (addresses & phone numbers)

Some downstream APIs require canonical, country-specific formats—for example, postal addresses or phone numbers. While a well-prompted slot often captures these correctly, you’ll sometimes need an extra normalization/validation step before you write.

Two patterns

- Preferred pattern: Call a purpose-built validation/normalization API if your system has one (e.g., an address verifier or telecom formatter).

- Use the built-in

mw.generate_text_actionto normalize user input into the exact shape your API expects, then pass that value to your write action. Keep Require consent on so users can review the normalized value before you send it.

Address normalization (with mw.generate_text_action)

mw.generate_text_action)Flow

- Collect

address_rawvia a slot (optionally collectcountry). - Normalize with a generative step.

- Show the preview (raw vs. normalized).

- Write using the normalized value.

Generative action (illustrative example)

Using built-in action mw.generate_text_action

system_prompt: >

"You are a data normalizer. Take a free-form address and return a single-line,

mailable address in the correct format for its country. Preserve semantics;

do not invent apartment/suite numbers. Output only the normalized address text."

model: "gpt-5-mini"

user_input: data.address_raw

Preview messaging

I’ll update the address to:

Original: “1600 Amphitheatre pkwy , Mountain View”

Normalized: “1600 Amphitheatre Pkwy, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States”

Proceed?

Phone number normalization (E.164)

Flow

- Collect

phone_rawand, if possible,countryorcountry_code. - Normalize to country (e.g.,

+16505550100) withmw.generate_text_action. - Preview, then write.

Generative action (illustrative example)

Using built-in action mw.generate_text_action

system_prompt:

RENDER():

template: >

Normalize the given phone number to country {{country}}. Validate the country/region;

return the core number only.

args:

country: data.country

model: '"gpt-5-mini"'

user_input: data.phone_raw

Preview messaging

I’ll update the phone to +44 20 7946 0958. Confirm?

When to prefer a deterministic API

If you have a first-party validator (postal service, compliance gateway, or carrier lookup), call it after slot collection and before the write. Use the API’s status to guide the UX:

Using a Decision Policy to restart Slot collection when the validation API says the value is invalid

- Collect the raw Slot value (e.g., address_raw or phone_raw)

- Call your validation API using that value

- Run a Decision Policy on the validator’s response for example

-

- If invalid → exit the plugin with the EXIT activity and have the user go through the flow again and let them know the address/number was invalid with any included suggestions using a content activity.

Updated 15 days ago